AWS S3: how to download file instead of displaying in-browser

As part of a project I’ve been working on, we host the vast majority of assets on S3 (Simple Storage Service), one of the storage solutions provided by AWS (Amazon Web Services).

Since this is a web project, we’ve then got a CloudFront CDN in front of the storage bucket, to ensure really fast delivery of content to users irrespective of their location on the planet. This is really rather easy to set up in AWS, and since I’ve been working on the opposite side of the world to the data centre for the last 3 months, I’ve really noticed the difference a CDN makes.

Uploading the assets to S3 is performed via the admin interface the team built. The files are uploaded directly to S3 using the signed URLs feature. This means that our app can pass a URL to the client, to which that browser can upload a file. This is a really helpful feature of S3, as our web-app never needs to see the data—it just gets uploaded straight to S3, rather than uploading to our app and then onto S3 later.

The filenames of uploaded image assets are irrelevant—they are used directly in the HTML, so end users won’t care about their names. This is a good thing, because careful choice of file names is the easiest way to prevent CDN caching problems:

Imagine I’ve uploaded a file named hello_sam.jpg to S3, and it gets served through the CDN. If I later discover a better image to use, so replace hello_sam.jpg with this new version, then how does the CDN know that it should re-request the new image from the source? It doesn’t. At some point each endpoint will request the image from the source, but in the meantime, different users around the world will be seeing a different image. This is incredibly hard to diagnose.

There are lots of different approaches we could have taken to avoid this issue, but we chose a very simple one—at upload time, we name the file with a UUID. These aren’t very user friendly, but it doesn’t matter, right?

Wrong.

Not all files are images

This approach works fine for all files that are consumed solely by a machine, but some of the assets are meant to involve the user in some respect. For example, PDFs of books and zip files of accompanying materials.

Providing a user with a PDF named 56174a62-c1f7-4b42-8e95-cad71237d123.pdf is a pretty shitty experience, when it should probably be called 101_Things You_Didn’t_Know_About_Cheese.pdf.

At this point, I can finally introduce the other problem associated with the system I’ve outlined thus far.

Dependent on the configuration of the browser, when a user visits the link pointing to that PDF (whether it be through S3 directly, or through the CDN in front of it), it’s quite likely to open up inline.

Another shitty experience.

101 Things You Didn’t Know About Cheese is a book that requires time to properly digest. And readers are sure to be reaching back into this weighty tome for years to come. They don’t want to view it in Chrome like an animal.

Wouldn’t it be great if there were a way to solve all of these problems:

- Retain the amazing file naming scheme to prevent CDN caching problems

- Automatically state that files should be

savoureddownloaded instead of read inline - Specify the filename of the downloaded file

Content Disposition to the Rescue

Every request that’s made over HTTP includes not only the content (the stuff we actually see), but also a load of headers. Think of these as like metadata fields that describe the nature and purpose of the request/response.

One of these headers is known as Content-Disposition, and it describes what the recipient should do with the content: should it be displayed inline in the browser, or downloaded as an attachment and saved as a file.

This is precisely what I’m looking for. It’ll allow me to keep the cache-busting file naming scheme, whilst also forcing downloads and specifying pretty file names.

The syntax is really simple:

Content-Disposition: attachment; filename="filename.jpg"

attachmentspecifies that the file should be downloaded instead of being displayed inline—which would be specified withinline.filename=specifies what downloaded file should be named.

Now that I know what the header should be, how can I get it into S3?

Specifying metadata in the S3 management console

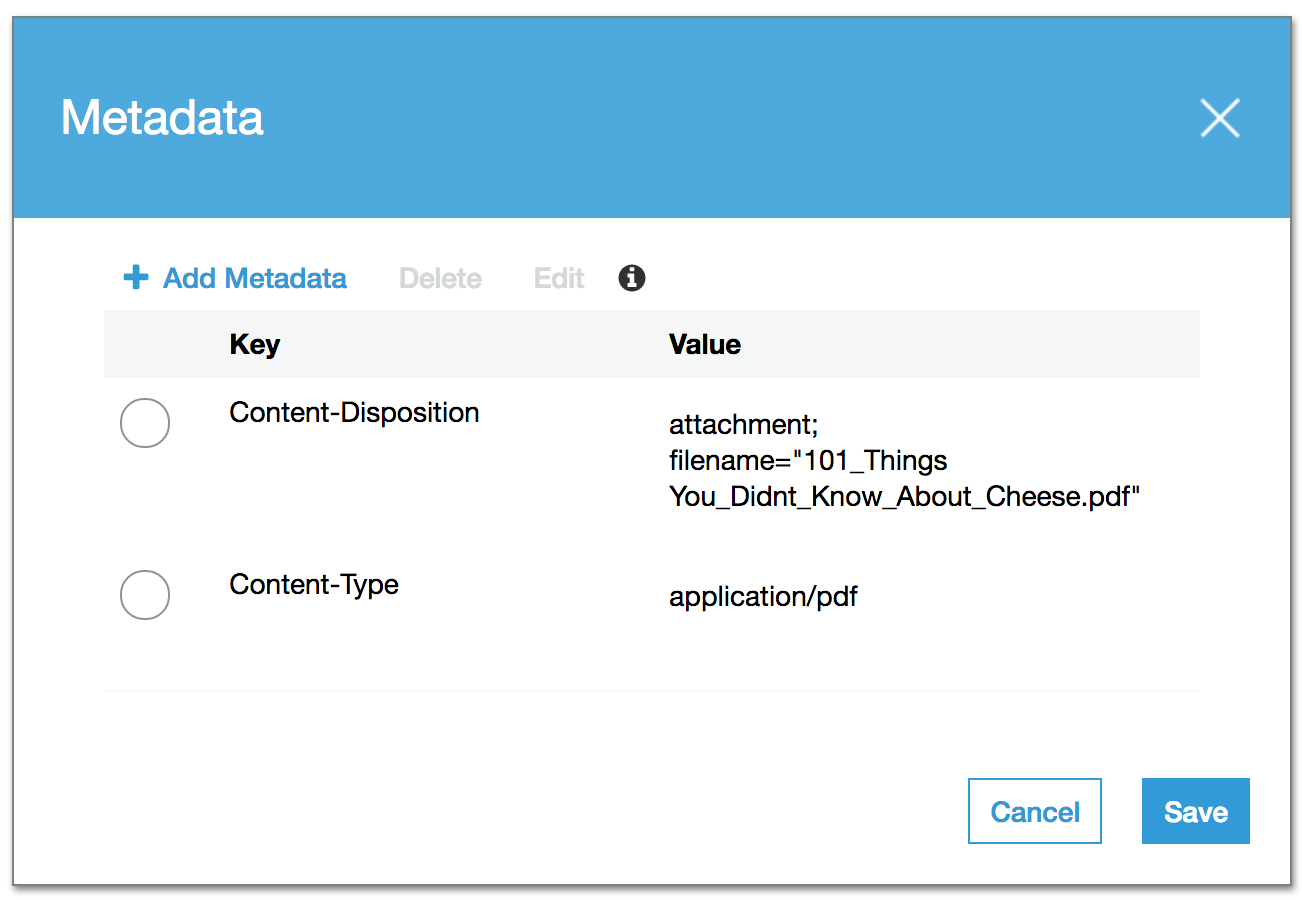

If you’ve already uploaded a file to S3, you can locate it in the S3 management console, and then see it’s metadata. These include the headers that will be sent to a client when it is requested.

Content-Type will already be populated—this would have been sent by your browser when you uploaded the file in the first place.

It’s relatively simple to add the Content-Disposition header to this metadata list too:

Note: This image is taken from what’s currently (December 2016) known as the “New S3 Management Console”. The old one looks quite different, but offers identical functionality in this regard.

Once you’ve made this update, the file will automatically be downloaded and have the friendly name next time you access it. Although, as ever, CDNs may take some time to update their caches, dependent on how you have it configured.

This can hardly be thought of as “scalable” though. Every time somebody uploads a file that should be downloaded through our admin interface, somebody has to pop into the S3 console and update the Content-Disposition header on that file. I certainly shan’t be signing up for that.

Specifying Content-Disposition at upload time

When you upload a file to S3, it stores the relevant headers as metadata. For example the Content-Type field that you saw in the previous section.

Therefore, we can reduce this problem to simply specifying the Content-Disposition header at the same time. Easy.

It is actually fairly easy, although it took me a while to figure out precisely what we needed to do.

As I mentioned before, we use signed S3 URLs for the uploading process. We have an endpoint in the app which generates this URL, passes it back to the client, which in turn attempts to upload the file the user selected to this URL.

We just needed to augment this process with the additional headers.

Our app is written in Ruby, so we use the AWS SDK for Ruby to generate the signed URL. In addition to specifying the uploaded filename, and the HTTP method, you can also add signed headers.

def self.sign(filename = nil)

return if filename.blank?

resource = Aws::S3::Resource.new

object = resource.bucket(ENV['AWS_BUCKET_NAME'])

.object("#{SecureRandom.uuid}#{File.extname(filename)}")

headers =

{ 'Content-Disposition' => "attachment; filename=\"#{filename}\"" }

{

signed_url: object.presigned_url(:put, presigned_params(headers)),

public_url: object.public_url,

headers: headers

}

end

def self.presigned_params(headers = {})

params = { acl: 'public-read' }

headers.each do |header, value|

params[header.parameterize.underscore.to_sym] = value

end

params

endThere are a few things to note here:

- The

signmethod is called at the point that a user requests to upload a new file. - It creates a UUID-based file name, with an extension that matches the original file.

- The

headershash defines theContent-Dispositionheader as specified above. This is sent back to the client, along with the signed URL for upload. - The signed URL uses the

presigned_urlmethod on the AWS S3 object, specifying that thePUTHTTP method will be used, and the additional parameters returned by thepresigned_paramsmethod. - The

aclvalue is not a header, but is represents a canned access policy—here choosingpublic-read. - Each of the headers is converted into a symbol that matches the form used by the AWS presigner.

This process generates a presigned URL, that specifies:

- The uploaded file name

- The ACL of the created file

- The HTTP method through which the file is uploaded

- The headers that are passed in the upload request

It’s important to note that the URL doesn’t provide all of these attributes, merely that they must be provided for the signature to match. Therefore we must send the headers along with the request.

We use jQuery on the front-end to create the request for the presigned URL, and can now use it to perform the upload itself:

$.ajax "/sign",

type: 'GET'

data: filename: file.name

success: (data, status, xhr) =>

$.ajax data.signed_url,

type: 'PUT'

contentType: file.type

headers: data.headers

data: @options.file

processData: false

success: (data, status, xhr) =>

console.log "Upload successful" The above CoffeeScript shows quite how simple this can be.

- First, a request to the

/signendpoint to get the presigned URL. This requires the name of the file that’s being uploaded - This invokes the Ruby

signfunction from above. When that returns, it provides a signed URL and a hash of headers - Perform a second AJAX call, this time to the presigned URL on AWS S3, pushing the file that needs to be uploaded. This uses the

PUTHTTP verb, and specifies theheadersthat were sent back from the Ruby. - If this succeeds, the code above just outputs an log message. In reality you would want to make sure to update your data model to include this newly uploaded file.

The really important part (and the part that I missed) was that I needed to specify the Content-Disposition header both to the URL signer, and at upload time.

When you try this out, and check out your uploaded file in the S3 management console, you’ll see that it has the Content-Disposition header set correctly in the metadata field. When you try and access the file in your browser, it’ll automatically download, with the filename you uploaded it as, even though it’s stored (and accessed) via a different filename.

Magic!

Final thoughts

I like AWS a lot—and we use a lot of their services. The reason it took me a while to get this figured out was because although the documentation is comprehensive, it’s often not all that clear. I hope that if you’re trying to achieve the same effect, and have happened across this post, that it helps you out.

Our file uploading system is a little more complex than this, because not all our files are publicly accessible, yet they are all accessible via the CloudFront CDN. I’ll add CloudFront signing for private content stored in S3 buckets to my list of things I might write about one day.

Big thanks to Mic Pringle for this post. We very much worked on this aspect of the site together, and now, without telling him, I’ve written it up as if it’s all my own work.

If you’ve ever read anything I’ve written in the past, or seen me speak, you’ll very quickly realise that nothing is my own work. My role is very much to find the most efficient way to join other people’s work together such that it kinda does what I want it to (=