Bringing dead projects back to life with Docker

This Saturday I found myself working on three separate ruby-on-rails projects. Three projects, with three different deployment strategies:

- The project I’m currently working on is Rails 5, and we have a Docker-based development and deployment strategy. When a branch is merged into the

developmentbranch, Docker hub builds a new image, which we can then deploy to the staging server via slack. Getting this set up was a fair amount of up-front work, but now we’ve got the Docker file, it’s fairly easy to maintain. - A project I started about 5 years ago that’s running happily on Heroku. This project was originally Rails 3.0, but I updated it to Rails 4.1 about a year ago. Since then I’ve not touched it much, but had to make a few small cosmetic changes this weekend. This was really easy to do with a Heroku deployment—I made the changes, deployed to staging to check they were OK, and then up to production. It would have been harder if I’d wanted to do spin up a local server, but the changes I made didn’t require it.

- An app I started about 4 years ago, and haven’t touched for nearly 3 years. This was written (and is still running) Rails 3.2, and uses Capistrano for deployment. All I wanted to do was update the mail server details. A three-line change. It took nearly 3 hours to complete.

I’d like to write about why the third option was such hard work, compared to making changes in the first two, and how I used Docker to ease the process.

The Problem

The codebase hadn’t been touched for three years. No dependency updates. No security patches. No updates to the version of Ruby.

This is a crappy way to make software. I don’t want to get into a discussion of this client, but rest-assured, I spent considerable energy trying to get across that you can’t just fire-and-forget with a web-app like this.

Needless to say, I lost those battles. Which is why it took me 3 hours to update 3 lines of code this weekend. It wasn’t even as if I had to find them. I knew exactly what to change. The challenge was getting them deployed.

This project is hosted on the client’s virtual host somewhere, so using Capistrano for deployment was a great option.

This’ll be fine though—I’ll grab the source, build the right Ruby version with rbenv, install dependencies with bundler and I’ll be done. Or not.

Installing Dependencies

I use macOS, so installing different versions of ruby is super-easy with rbenv:

$ rbenv install 1.9.3-p327That went without a hitch, barring the warnings that this is really out-of-date and unsupported.

Then I can go ahead and install the dependencies. Since bundler creates a Gemfile.lock, you can be certain that precisely the same versions of your gems will install irrespective of when you last used them. Updating gems requires you to issues a specific update command.

That means that all you have to do is:

$ bundle installOf course it didn’t work. When I last installed this specific gemset, Xcode still included a GCC buildchain. It was replaced with LLVM in 2013, which caused the native extensions for one of the gems not to compile.

Imagine an interlude here where I attempt installing just the gems I think I need, manually chasing the dependency chain. And then I spend a while reading through old stack overflow answers trying to find answers to problems that don’t say “update to this version”. I’m not going to write about it—you’ve all done it. You know how dull it is.

I should point out at this stage that I didn’t really want to get into updating this project. Everything needed updating to much more recent versions, and I estimate it was at least a couple of days’ work. That is definitely not what the client wanted.

I realised I was about to jump headfirst into a rabbit hole much sooner than I usually do—at the point I was using homebrew versions to find old versions of dependencies I knew I should stop.

Docker to the rescue

I’ve been doing a lot of work in Docker recently and have found the experience to be mostly very positive. It’s great for ensuring that we run the same stack in development, staging and production. That and the fact that we can be sure that we’re all running precisely the same versions of everything.

Although I didn’t need these features for my project revival, I realised that I could use Docker to create an image that reflected the exact dependencies I needed, irrespective of how old they were. And when I was done, I could just throw it away. I wouldn’t be randomly installing old crap into the host OS until I could get the app to deploy—it would all just be in a throwaway container. Perfect!

But wait.

What if, rather than building this image myself, somebody had already done it for me?

DockerHub has official builds for a huge range of projects, one of which is Ruby. So if I can find an image that contains an old enough version of Ruby, I’ll be well on my way.

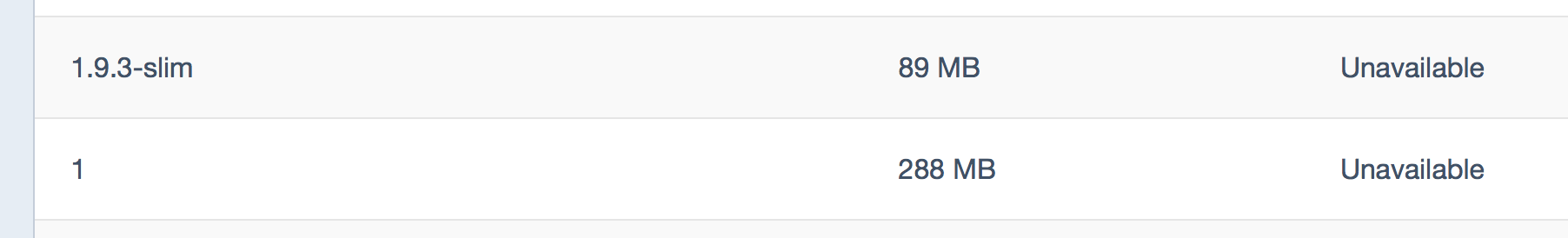

It’s not in the supported list of versions, but the tag is there. That’ll do.

Note that I chose the full distro version here, because I wanted to be sure that everything required to build the native extensions was there. If I were deploying this in a Docker container, I’d look to choose a smaller base image.

Now I can run up a shell in this container and check the install version of ruby:

$ Docker run -it ruby:1 bash

root@b13634320876:/# ruby --version

ruby 1.9.3p551 (2014-11-13 revision 48407) [x86_64-linux]OK—that version of Ruby will do just fine. I’ve now got a Docker container running with the correct version of ruby. But how can I get my app into it?

Mounting a local directory

You can absolutely use Docker commands to mount a local directory inside the container. However, I’m a fan of Docker compose. This allows you to specify a system of containers and their dependencies in a declarative manner. This is done in a YAML file, and is really easy to understand.

Although this use case is very simple, it saves me having to remember Docker commands—instead relying on the Docker-compose.yml file to do the work:

version: '2'

services:

app:

image: ruby:1

volumes:

- .:/opt/webappThis specifies a single service in compose. It uses the same image I just used, and mounts the current directory to the /opt/webapp point within the container.

Running this up is easy:

$ Docker-compose run app bashOnce in there I was able to navigate to the /opt/webapp directory and bundle install all the dependencies.

The great thing about mounting the directory in this manner, is that you can continue to edit your files in the host OS, including doing git operations etc.

This is the approach we’re using for the app we’re working on at the moment. It has some downsides, but on the whole, it’s a great way to develop locally.

So what?

What was the point of this post? I wanted to highlight a slightly different use for Docker. There’s a huge focus on building these massively scalable, self-healing infrastructures. Sure they sound sexy, but I don’t think all that many of us need those features.

But that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t take a look at what Docker, or other containerisation technologies, have to offer. This example of getting a dead app back up on its feet long enough to patch some settings on a live app is a perfect demonstration of what else you can do.

Hopefully you’ll see another side to Docker too.